How Garvey’s Newspaper United a Diaspora

Before there was Black Twitter, there was a Black newspaper in Harlem carrying the voices of a scattered people across the world.

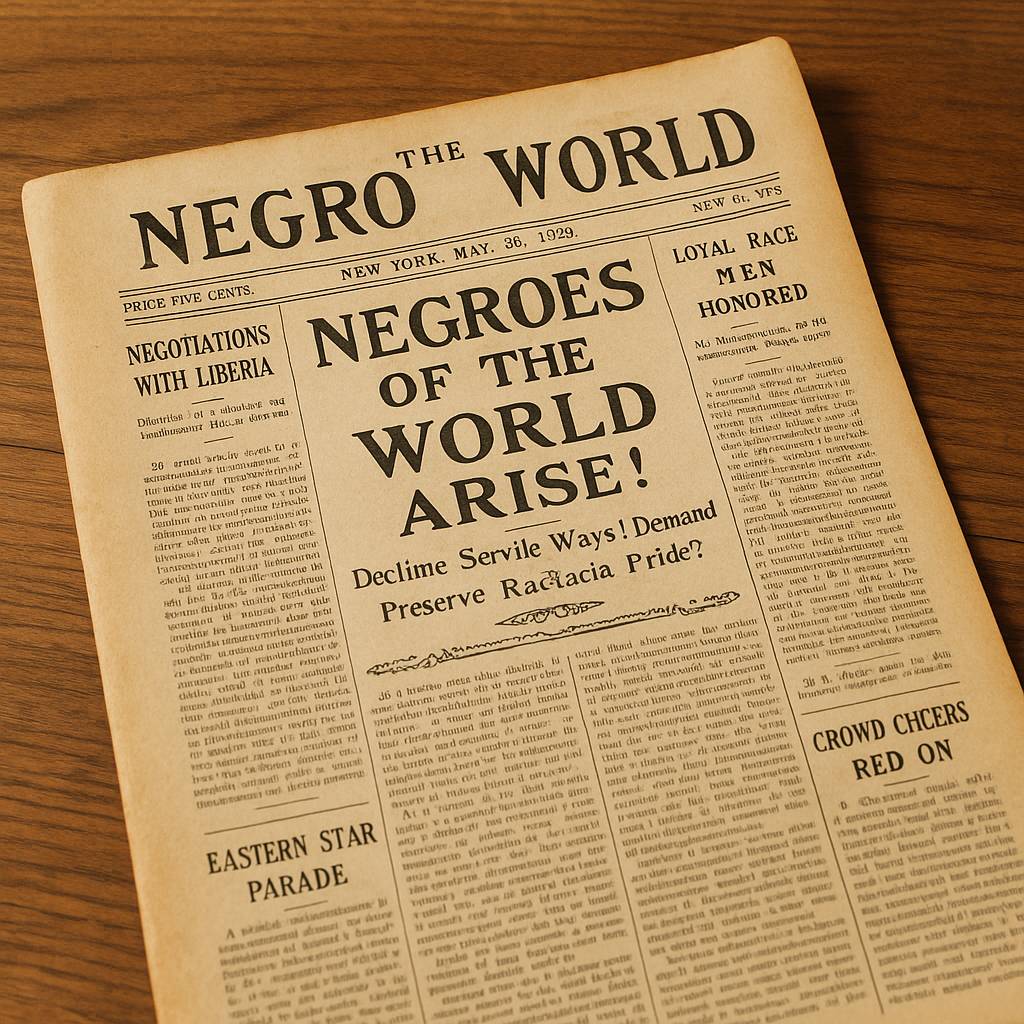

Long before livestreams, podcasts, or viral posts, Marcus Garvey understood a simple truth: if you control the story, you control the future. In 1918, as his Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) was expanding in New York and abroad, he launched the Negro World, a weekly newspaper published in Harlem. For the price of a few cents, readers could buy a passport into a larger Black universe — one that stretched from Southern sharecropper farms to Caribbean docks and African port cities.

Between 1918 and the early 1920s, the Negro World did more than report news. It taught history, preached pride, spread Pan-African ideas, and offered a platform for voices usually silenced by white-owned media. It was the movement’s megaphone, classroom, and stage all in one. In many ways, it was the internet of Garvey’s age for Black people.

- The Negro World was the official newspaper of the UNIA, founded in 1918 in Harlem.

- It combined news, politics, culture, women’s columns, and literature from across the Diaspora.

- Colonial governments tried to ban it, fearing its impact on African and Caribbean subjects.

- Women, especially Amy Jacques Garvey, played a major editorial and literary role.

- Its legacy lives on in Black media, radical journalism, reggae lyrics, and Pan-African thought.

The Birth of the Negro World in Harlem

When Garvey first arrived in the United States, he quickly saw the importance of the Black press. Papers like the Chicago Defender and the Pittsburgh Courier were already circulating migration stories and civil rights news. But Garvey wanted something more: a paper explicitly rooted in Pan-African ideas and directly linked to his growing global organization.

In 1918, the UNIA launched the Negro World out of Harlem. From the start, it was conceived not just as a local newspaper but as an international organ — a mouthpiece for the UNIA’s motto: “One God! One Aim! One Destiny!”

Garvey’s Editorial Vision

Garvey saw the paper as:

- A teacher — educating readers in history, geography, and politics.

- A trumpet — sounding calls for self-reliance, race pride, and African redemption.

- A mirror — reflecting images of Black heroes, achievements, and everyday excellence.

At a time when most mainstream newspapers either ignored Black people or portrayed them as caricatures, the Negro World declared, week after week, that Black life was the center of its universe.

“The Negro World is the paper of the new Negro— the Negro who will not apologize for his existence, but will organize it.” — Marcus Garvey, paraphrased from early editorials

- Founded in 1918, the Negro World became the UNIA’s official press organ.

- It was designed from day one as a global, not just local, publication.

- Garvey saw it as a tool to educate, inspire, and mobilize the African Diaspora.

Inside the Pages: News, Culture, and Uplift

The strength of the Negro World was its variety. A single issue could contain political editorials, business tips, poems, news dispatches from Africa, reports on UNIA meetings, and even children’s pieces. It was a world in miniature.

Front-Page Fire: Editorials and Headlines

The front page usually carried:

- Lead editorials from Garvey or senior leaders, explaining UNIA positions.

- Headlines about racism, colonial injustice, and resistance around the globe.

- Reports from major UNIA conventions, parades, and business ventures like the Black Star Line.

These pieces framed Black issues as international rather than isolated. A lynching in the American South and a labor strike in the Caribbean were treated as chapters in the same story — a story of a people pushing against oppression.

Culture Corner: Poems, Stories, and Sermons

Beyond hard news, the Negro World was a crucial outlet for Black creativity. It featured:

- Poetry that adopted African images, Biblical references, and Garveyite language of redemption.

- Short stories exploring themes of migration, colorism, faith, and love under racism.

- Sermons and reflections that blended Christian theology with Pan-African hope.

Many aspiring writers got their first exposure in its pages. For readers in rural areas or colonial towns without libraries, the paper itself was a mobile library.

Education and Economic Advice

The paper also included practical content:

- Columns on starting small businesses, saving money, and buying property.

- Profiles of Black professionals — doctors, lawyers, teachers — as role models.

- Historical articles on African empires and leaders, restoring timelines erased in mainstream schooling.

“In a few pages, the Negro World did what whole school systems refused to do — teach Black people that they came from builders, not from chains.” — Reggae Dread Archive Note

- The paper mixed politics, culture, and practical advice in one package.

- It introduced readers to African history and global Black achievements.

- It nurtured a generation of Black writers, thinkers, and entrepreneurs.

The Women Behind the Words

While Garvey’s name is most associated with the Negro World, women played a vital role in its content and tone. Chief among them was Amy Jacques Garvey, who became one of the most influential Black women editors of the era.

Amy Jacques Garvey’s Editorial Power

Amy Jacques started as a secretary within the movement but soon took on editorial duties. She:

- Edited the women’s page, which highlighted issues specific to Black women.

- Published essays encouraging women to be politically active, educated, and economically independent.

- Compiled Garvey’s speeches into collections that would reach readers long after he was imprisoned or deported.

Through her pen, she broadened Garveyism’s scope. The movement became not only about race pride and Africa, but also about the role of women as thinkers, workers, and nation-builders.

“We are tired of hearing Negro men say, ‘There is a better day coming,’ while they do nothing to usher in the day.” — Amy Jacques Garvey, paraphrased from her columns

Other Women’s Voices

Other women used the paper to:

- Write letters to the editor demanding respect within families and communities.

- Share poems about motherhood, labor, and resistance.

- Report on women-led UNIA branches and charitable projects.

In a media world that heavily censored Black women’s perspectives, the Negro World gave them a platform — and, in the process, laid groundwork for later Black feminist thought.

- Amy Jacques Garvey helped shape the intellectual direction of Garveyism.

- The women’s page gave space to concerns often ignored by male leaders.

- The paper amplified Black women’s voices long before it was common to do so.

Circulation, Smuggling, and Censorship

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Negro World was how far it traveled. Although printed in New York, it reached:

- Caribbean islands like Jamaica, Trinidad, Barbados, and Belize.

- African territories such as Gold Coast (Ghana), Nigeria, Sierra Leone, and South Africa.

- Black communities in Central and South America, from Panama to Brazil.

- Black dockworkers and seamen in Europe and the UK.

Seamen, missionaries sympathetic to the cause, and UNIA agents served as couriers. Copies were passed hand to hand, read aloud in bars and barber shops, and shared in secret reading circles.

Why Colonial Governments Feared the Paper

The very reach of the paper made colonial authorities nervous. Reports praising African resistance or criticizing white supremacy were seen as “seditious.” As a result:

- Governors in British and French colonies attempted to ban the paper.

- Customs officials seized copies at ports and post offices.

- Possession of the Negro World could label someone a troublemaker in the eyes of the state.

“When the Negro World arrives, the natives begin to talk too much.” — Paraphrased from a colonial administrator’s complaint

Smuggling as Resistance

Bans did not stop the circulation — they merely forced it underground. Sailors would:

- Hide copies inside crates of food or clothes.

- Slip issues to trusted dockworkers who would then distribute them inland.

- Tear out key articles and pass them around separately to reduce risk.

In this way, reading the Negro World became an act of quiet rebellion. It created a sense of shared danger and shared discovery across continents.

- The paper’s circulation network connected Black people across oceans.

- Colonial states feared its Pan-African message and tried to suppress it.

- Smuggling turned the act of reading into a political act.

A Bridge Across the Diaspora

Perhaps the most important function of the Negro World was psychological: it convinced far-flung communities that they were not alone. A reader in Lagos could see reports from Harlem; a worker in Panama could read about strikes in Trinidad; a teacher in Jamaica could follow anti-colonial debates in West Africa.

Letters, Reports, and Local Correspondents

UNIA divisions and sympathizers sent in:

- Minutes of local meetings and parades.

- Accounts of racism and resistance in their towns.

- Obituaries, wedding notices, and school achievements.

In this way, the paper functioned like an early social network — a slow-motion timeline where communities posted updates on their struggles and victories.

Translation and Multilingual Reach

While published in English, its ideas traveled in many languages. Local activists would:

- Translate key articles into French, Spanish, or African languages.

- Summarize content orally at meetings attended by non-English speakers.

- Adapt editorials into sermons, speeches, and songs.

The result was a multi-lingual conversation about freedom, all anchored in a paper printed on West 135th Street in Harlem.

“Negro World made us feel that we were not just natives of a colony, but citizens of a scattered nation.” — Caribbean reader, later interviewed

- The paper allowed distant communities to see themselves in a shared story.

- Local correspondents turned it into a grassroots global network.

- Translations and oral reports expanded its reach far beyond English readers.

Competition, Critics, and Internal Debate

The Negro World was not the only Black newspaper of its time, nor was it above criticism. Other editors and leaders debated Garvey’s methods, questioned the finances of the UNIA, or disagreed with his emphasis on a return to Africa.

Rival Press and Intellectual Disputes

Some rival Black papers:

- Accused the UNIA of exaggerating its membership and financial strength.

- Warned readers against investing in the Black Star Line.

- Argued for integrationist strategies over Garvey’s nationalist approach.

These criticisms sometimes appeared within the Negro World itself in the form of rebuttals, editorials, and open letters. The debate, though heated, signaled a maturing Black public sphere — one where ideas were contested in print, not just whispered in private.

The Impact of State Repression

When Garvey was prosecuted and eventually imprisoned, the paper came under greater pressure. Financial strain, leadership upheaval, and constant surveillance all took a toll. Publication became irregular, and some readers drifted toward other outlets.

Still, even as the original Negro World declined, its example inspired other Black newspapers, journals, and newsletters to take up a similar role: connecting local struggles to a global narrative of Black freedom.

- The paper was part of a wider ecosystem of Black journalism.

- Critiques reflected genuine disagreements about strategy and leadership.

- Despite state repression, the idea of a global Black press survived and evolved.

Legacy: From Harlem Print to Global Consciousness

The physical pages of the Negro World grew yellow and fragile with time, but its influence seeped into many corners of the twentieth century. Leaders of African independence movements remembered reading it as students. Caribbean radicals recalled hiding copies under their mattresses. In Jamaica, echoes of Garvey’s newspaper themes can be heard directly in reggae and Rastafari teachings.

From Headlines to Lyrics

Decades after the paper’s peak, reggae artists like Burning Spear, Big Youth, and Bob Marley would:

- Quote Garvey’s lines about mental emancipation and self-reliance.

- Sing about Africa as home, echoing the paper’s Pan-African content.

- Use song as the new “Negro World,” spreading messages faster than print ever could.

In that sense, the reggae record became the spiritual descendant of the Garveyite newspaper: a low-cost, widely circulated medium carrying radical ideas across borders.

Lessons for Today’s Black Media

For modern platforms — from independent blogs to podcasts and YouTube channels — the Negro World offers enduring lessons:

- Own the platform: Don’t rely solely on hostile or indifferent mainstream outlets.

- Center community voices: Let ordinary people report on their own realities.

- Think globally: Connect local issues to the larger history and geography of the African Diaspora.

- Blend culture and politics: Use art, humor, and storytelling alongside polemics.

“Negro World showed that a newspaper could be more than ink on paper; it could be a drumbeat for a scattered family finding its rhythm again.” — Reggae Dread Commentary

The Negro World transformed the Black press into a global Pan-African classroom. It linked people who had never met, giving them a shared sense of destiny — a legacy that still informs how Black media, music, and movements communicate today.

To understand how this powerful voice in print fit into the wider Garvey story, it’s important to see its relationship to the UNIA’s mass gatherings, the spectacle of Harlem’s parades, and the fierce battles with U.S. authorities. Those threads continue in the other chapters of this ReggaeDread series on Garvey in New York.

Read next in the “Marcus Garvey in New York (1916–1924)” series: