How the FBI and Hoover Tried to Silence a Black Visionary

Inside the showdown between Marcus Garvey and J. Edgar Hoover — the battle that turned Black nationalism into a federal “problem.”

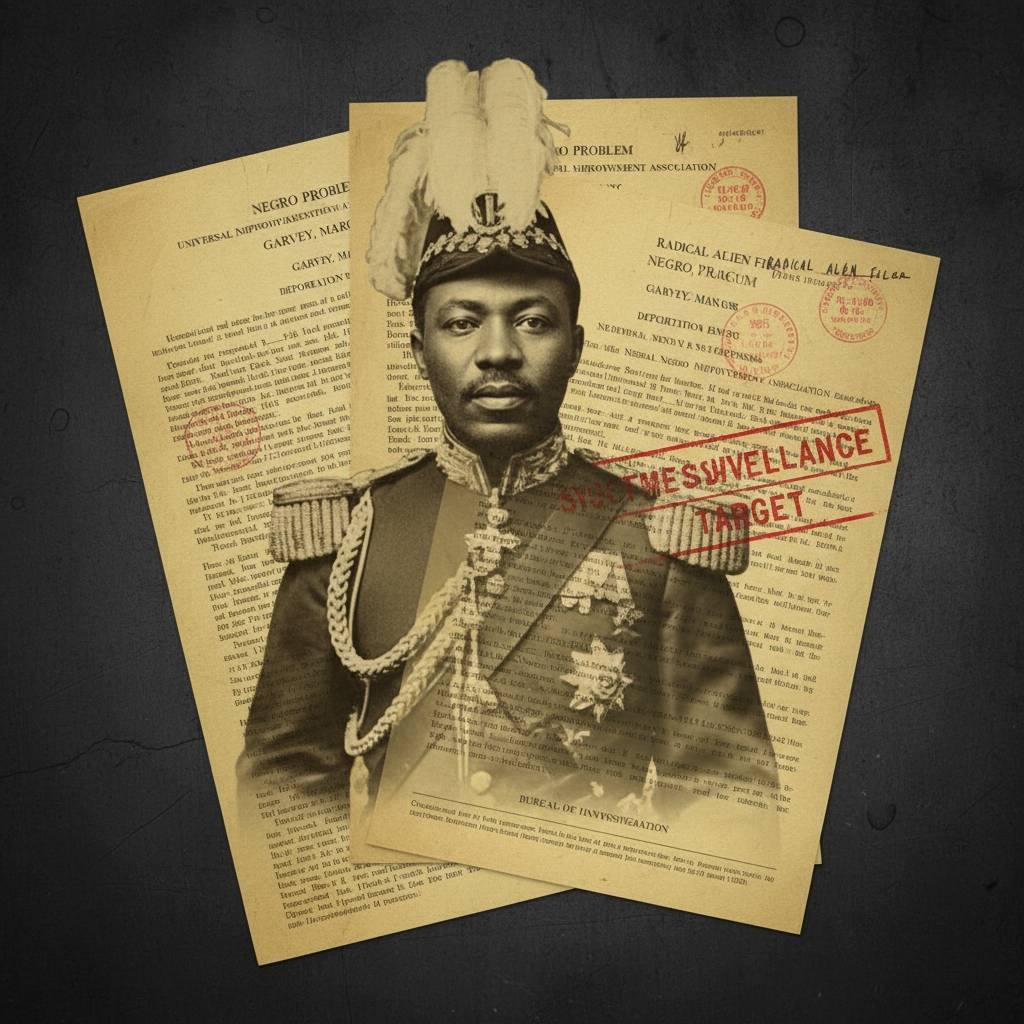

By the early 1920s, Marcus Garvey had become impossible to ignore. His Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) claimed millions of supporters, his Black Star Line promised economic independence, and his speeches thundered across Harlem and beyond. To his followers, he was a prophet of self-determination. To J. Edgar Hoover and the young Bureau of Investigation, he was something else entirely: a threat.

This article follows the arc of that confrontation — how federal surveillance, courtroom tactics, and media attacks converged on one man and one movement. It’s not just the story of Garvey vs. the FBI; it’s a blueprint for understanding how Black power has been monitored and criminalized in the United States ever since.

- Garvey’s rise in Harlem triggered intense anxiety inside the U.S. Justice Department.

- J. Edgar Hoover’s Bureau targeted Garvey with informants, surveillance, and legal harassment.

- The mail-fraud case against Garvey grew from the struggles of the Black Star Line.

- The trial and conviction were as much political as legal, sending a message to future Black leaders.

- Garvey’s resistance helped shape later movements’ understanding of state power and repression.

- From Harlem’s Hero to Washington’s “Problem”

- Hoover’s Bureau and the Birth of “Negro Subversion” Files

- Informants, Infiltration, and the Search for a Crime

- The 1923 Trial: Garvey in the Dock

- Propaganda, Press, and the Battle for Public Opinion

- Prison, Commutation, and Deportation

- Legacy: What “Garvey vs. the System” Teaches Us Today

From Harlem’s Hero to Washington’s “Problem”

The seeds of the Garvey–Hoover conflict were planted in Garvey’s spectacular rise. By 1919, Harlem’s streets had seen UNIA parades with marching bands, uniforms, and flags of red, black, and green. The Black Star Line stock drive had stirred working-class investors from New York to the Caribbean. The Negro World newspaper traveled clandestinely into colonies where its message made colonial governors nervous.

From the perspective of Washington, this was not just a social movement. It was a mobilization of Black people across national borders — during a period when the U.S. government was already jittery about “radicals,” workers’ strikes, and post-war unrest. A Black leader speaking in terms of nationhood, race pride, and global unity looked dangerously “un-American” to officials tasked with keeping order.

“The Bureau should endeavor to deport Garvey… his activities are detrimental to the best interests of the colored race, and are likely to result in trouble for the Government.” — J. Edgar Hoover, internal memorandum

For Hoover, Garvey represented an early opportunity to prove the value of domestic intelligence work. If he could bring down the most visible Black nationalist in America, he would cement his reputation and define the Bureau’s role in managing “subversive” threats.

- Garvey’s movement grew into a global network centered in Harlem.

- The U.S. state read Black pride as potential disorder.

- Hoover saw Garvey as a test case for a new internal security apparatus.

Hoover’s Bureau and the Birth of “Negro Subversion” Files

The early Bureau of Investigation (before it officially became the FBI) was still defining its scope. Initially focused on wartime espionage, it quickly pivoted to monitoring domestic dissent: labor unions, socialists, and anyone deemed “unpatriotic.” Within this logic, a charismatic Black leader capable of filling Madison Square Garden with cheering supporters fell under the same umbrella.

Hoover authorized the creation of dedicated files on Black organizations — including the UNIA — under categories like “Negro agitation” or “Negro subversion.” Agents clipped articles, collected speeches, and compiled reports from local police departments and southern sheriffs wary of “outside agitators.”

Defining a New “Threat” Category

What made Garvey stand out in these files was not only his rhetoric, but his infrastructure. He wasn’t just giving stirring speeches; he was:

- Running a global membership organization with branch offices and officers.

- Publishing an international newspaper viewed as “seditious” by colonial authorities.

- Launching the Black Star Line, a commercial enterprise that symbolized economic independence.

For a government used to dealing with isolated activists, this level of institution-building was alarming. In their reports, agents began to portray Garvey as a figure whose power came from his ability to organize, not just to speak.

- Hoover’s Bureau expanded from wartime spying to monitoring domestic “radicals.”

- Garvey’s UNIA became a primary focus of “Negro subversion” surveillance.

- The state’s concern centered on organization and institutions, not only words.

Informants, Infiltration, and the Search for a Crime

Hoover could not simply arrest Garvey for being popular or controversial. He needed a criminal charge. The Bureau’s strategy was therefore to watch, infiltrate, and wait for either a mistake or a technical violation they could magnify into a felony.

Planting Eyes and Ears Inside the UNIA

Agents recruited informants from within Black communities, including some who attended UNIA meetings and conventions. They were instructed to:

- Take notes on speeches and record any “inflammatory” remarks.

- Report on financial dealings, including Black Star Line stock sales.

- Track conflicts between Garvey and other Black leaders, feeding rumors where possible.

Reports flowed back to Washington, creating a portrait of a movement full of energy, ambition, and inevitable human mistakes. But none of that, in itself, was a crime.

The Black Star Line as Legal Opening

The turning point came when prosecutors argued that promotional materials for the Black Star Line had advertised ships that were not yet fully secured. This became the basis for a mail-fraud charge: that Garvey had used the postal service to circulate “false” information to investors.

It was a fragile case. Many businesses exaggerate, rebrand, or adjust plans as they grow. But Garvey’s case was not just about business law. It was a chance to say: independent Black enterprise at this scale would be punished more harshly than its white counterparts.

“We were not prosecuted because of fraud, but because we dared to dream ships into the hands of Negroes.” — Paraphrased from Garvey’s prison writings

- The Bureau placed informants inside UNIA spaces to gather data and sow division.

- Mail-fraud charges grew from the Black Star Line’s promotional struggles.

- The law became a tool for political control, not neutral justice.

The 1923 Trial: Garvey in the Dock

In 1923, Marcus Garvey went on trial in New York federal court. The case drew immense public attention. Supporters stood outside the courthouse, UNIA members in uniform filled the gallery, and newspapers speculated about what a conviction would mean for the movement.

Garvey as His Own Lawyer

Making a controversial move, Garvey chose to represent himself. He believed that no one could speak for his intentions better than he could. In the courtroom he:

- Cross-examined witnesses about their motives and biases.

- Argued that the Black Star Line was a good-faith attempt at enterprise, not a scam.

- Linked the prosecution to a broader pattern of racism and fear of Black progress.

Yet the odds were stacked against him. The jury was all white. The climate of the time was hostile to Black assertion. The technical nature of the charges — focusing on stock circulars and ship valuations — allowed the prosecution to sidestep the larger political context.

“I do not stand here as an accused man for crime, but as one who has dared to preach liberty for 400 million Negroes.” — Marcus Garvey, addressing the court

Garvey was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison. For the Bureau, it was a triumph. For the UNIA, it was a wound — but also a rallying point. Many members saw the verdict as proof that the system would never tolerate a Black leader who thought on a global scale.

- Garvey’s self-representation turned the trial into a political platform.

- An all-white jury weighed complex business charges in a racially charged era.

- Conviction served as both punishment and warning to other Black leaders.

Propaganda, Press, and the Battle for Public Opinion

The trial wasn’t only fought in court. It was fought in newspapers, rumor networks, and whispers in barber shops. The U.S. government understood that if it could tarnish Garvey’s reputation, it could weaken the UNIA from within.

Media as a Weapon

Mainstream papers often ridiculed Garvey, depicting him as a buffoon or con man. Political cartoons portrayed him in exaggerated uniforms, mocking his titles and pomp. Articles emphasized financial missteps while ignoring the scale of what he had attempted: a Black-owned global enterprise in an openly racist economy.

At the same time, Hoover’s Bureau quietly leaked information, shaping the storyline. Mismanagement became “fraud.” Ambition became “delusion.” A movement fighting for dignity was recast as a dangerous cult under a reckless leader.

Garvey’s Counter-Narrative in the Negro World

Garvey answered these attacks through the Negro World. Editorials framed the trial as a test of Black rights, not simply his personal fate. Writers reminded readers of the ships purchased, the conventions held, the branches opened around the world. They insisted that even if the man fell, the idea could not be jailed.

“They hope to bury Garvey, but they forget that seeds are also buried before they rise.” — UNIA supporter, quoted in Negro World

- Newspapers played a key role in shaping how the public saw Garvey.

- Government leaks helped paint the UNIA as inherently suspicious.

- The Negro World became a vital counter-voice for the Diaspora.

Prison, Commutation, and Deportation

In 1925, Garvey entered Atlanta Federal Penitentiary. For many movements, the imprisonment of their central figure would mean collapse. Yet from prison, Garvey continued to issue statements, organize supporters, and reflect on strategy. His body was confined, but his words traveled.

Letters from Behind Bars

Garvey wrote letters to UNIA branches and to the broader community, urging discipline and perseverance. He interpreted his incarceration as proof of the movement’s power: “If we were insignificant, they would not bother with us.” In this way, he converted suffering into a narrative of sacrifice.

Meanwhile, campaigns for his release gained momentum. Petitions circulated. Supporters lobbied politicians, arguing that his sentence was excessive and politically motivated.

Commutation and Forced Exit

In 1927, President Calvin Coolidge commuted Garvey’s sentence. But the reprieve came with a catch: the U.S. government immediately moved to deport him. Garvey was placed on a ship and sent back to Jamaica, barred from re-entering the country that had been the epicenter of his movement.

He arrived in Jamaica no longer as a rising star, but as a controversial icon — admired, criticized, and forever marked by his clash with the American state. Yet even in deportation, he refused to frame the episode as defeat.

- Garvey used prison to deepen his role as a symbol, not just an organizer.

- Public pressure contributed to the commutation of his sentence.

- Deportation removed him physically from Harlem but could not erase his influence.

Legacy: What “Garvey vs. the System” Teaches Us Today

Looking back from the twenty-first century, the clash between Marcus Garvey and J. Edgar Hoover reads like a prequel to later histories. The tactics tested against Garvey — infiltration, surveillance, criminalization, and media framing — would reappear in operations against Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., the Black Panther Party, and many others.

Garvey’s experience teaches several enduring lessons:

- Visibility invites scrutiny: The more successful a Black movement becomes, the more likely it is to be monitored.

- The law is political: Legal charges can be deployed selectively to break organizations that challenge power structures.

- Symbolism matters: Even when institutions are damaged, symbols — like Garvey’s name, flag, and ideas — can outlive repression.

For today’s organizers and artists, “Garvey vs. the System” is not just a history lesson. It is a mirror. It asks: How do you build strong, transparent institutions that can withstand attack? How do you tell your own story before others write it for you? And how do you hold on to vision when the system tries to turn you into a cautionary tale?

Garvey lost the legal battle but won a larger war of memory. His confrontation with the FBI exposed the lengths to which power will go to contain Black freedom — and inspired future generations to organize with eyes wide open.

The next chapters of this series follow how Garvey’s ideas continued to move people even after his deportation, and how the culture of Harlem kept his spirit alive. To understand the full arc, move forward to the closing phases of his U.S. journey and the triumph of his legacy.

Read next in the “Marcus Garvey in New York (1916–1924)” series: