Hope, Identity, and the Search for a Homeland

When millions moved north and across oceans, Garvey gave them a flag, a story, and a sense of home they could carry in their hearts.

Between 1916 and 1930, more than a million Black Americans left the cotton fields and small towns of the U.S. South and headed to cities like Chicago, Detroit, and New York. This mass relocation — the Great Migration — reshaped America’s demographics and culture. At the same time, ships carried thousands of Caribbean migrants to those same cities, especially Harlem. They were all searching for something: safety, wages, opportunity, and a place to breathe.

Into this moving, unsettled world stepped Marcus Garvey, the Jamaican-born leader of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). In New York, his message of race pride, global unity, and “Africa for the Africans” did more than inspire. It gave the migrating generation a story big enough to hold their losses and their dreams — a story of homeland that stretched far beyond any single city.

- The Great Migration and Caribbean immigration turned Harlem into a global Black capital.

- Garvey’s UNIA offered migrants community, structure, and a sense of destiny.

- “Africa” became both a literal homeland and a symbol of sovereignty and pride.

- UNIA halls functioned as churches, schools, job centers, and embassies for the displaced.

- Garveyism helped migrants reinterpret their journey as part of a larger liberation story.

The Great Migration and Harlem’s Transformation

The Great Migration was, at first glance, about work. Northern factories needed labor; Southern Black workers needed escape from lynching, debt peonage, and Jim Crow humiliation. Families sold what little they had, bought train tickets, and headed north with rumors of jobs and better schools in their ears.

But once they arrived, many migrants realized they had not reached paradise — just a different kind of struggle. Housing was overcrowded. Jobs were dirty and often dangerous. Racism hadn’t disappeared; it had simply changed uniform. Still, there was a crucial difference: in places like Harlem, Black people were a visible majority for the first time in modern urban history.

Churches multiplied. Storefronts with Black owners appeared. Musicians and poets crafted new sounds and stories. The sense that “we are many” electrified the streets.

“The train north didn’t just change our address. It changed our imagination.” — Reggae Dread Archives

- The Great Migration uprooted millions from the rural South into Northern cities.

- Harlem became a symbolic capital of Black modern life.

- Amid opportunity and hardship, migrants were ready to hear a bigger story about who they were.

Caribbean Arrivals and a New Black Mosaic

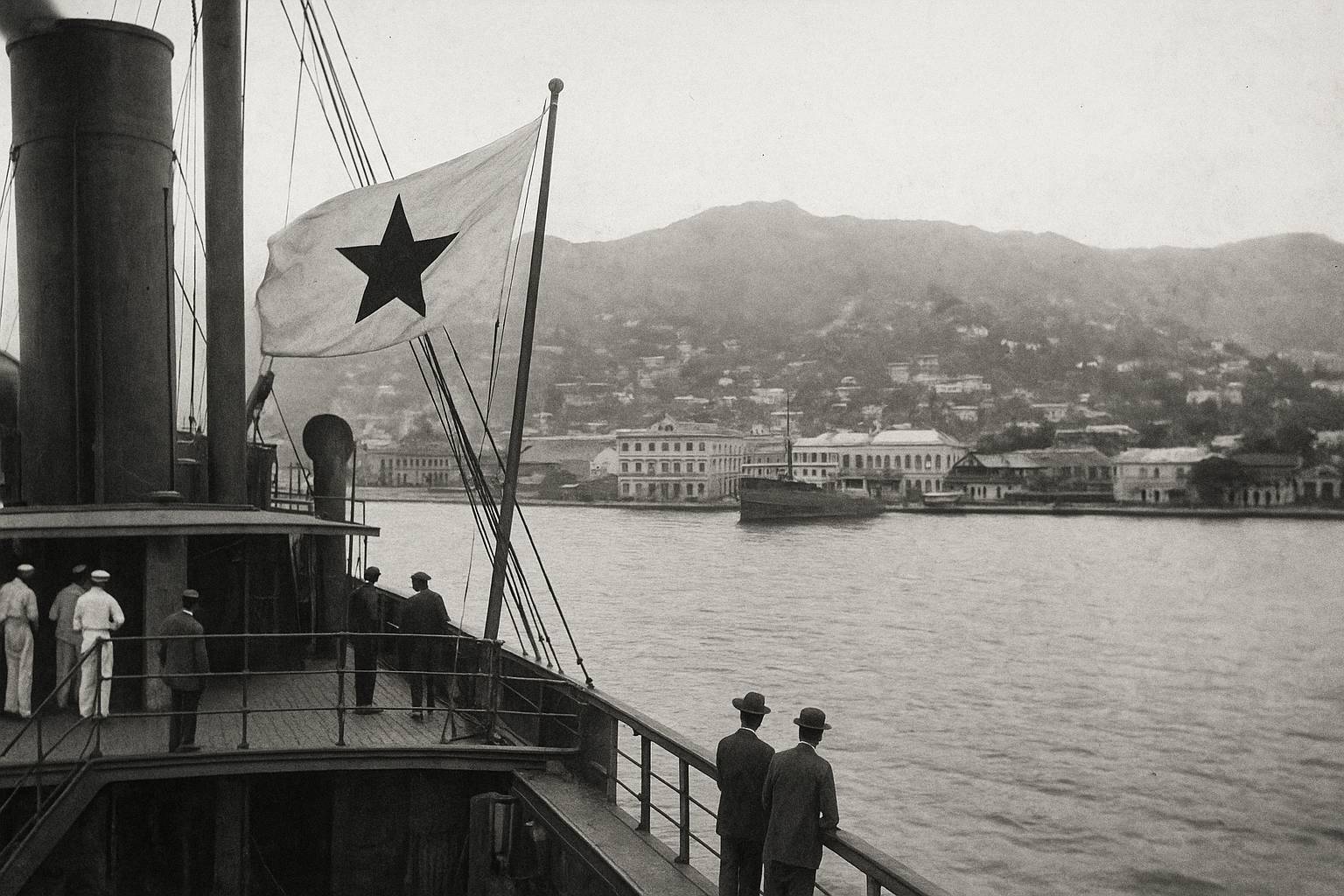

While Southern trains pulled into Northern stations, steamships from the Caribbean anchored in New York Harbor. On board were Jamaicans, Barbadians, Trinidadians, Grenadians, Belizeans, and others, many with experience navigating colonial bureaucracies, trade, and political debate.

They came with their own cultures—patois, calypso, folk religions, British-style schooling—and found themselves shoulder to shoulder with Southern migrants whose lives had been shaped by sharecropping, spirituals, and Jim Crow. Harlem became a mosaic of accents, cuisines, and worldviews.

“The Caribbean gave Harlem its accent; the South gave it its soul.” — Harlem oral history, 1938

- Caribbean and Southern Black migrants met in Harlem in unprecedented numbers.

- Each group brought different experiences of racism and empire.

- The mix created fertile ground for a new, global sense of Black identity.

When Garvey Met the Migrants

Marcus Garvey arrived in the United States in 1916. He saw immediately that this was not just a country — it was a crossroads. Harlem, in particular, struck him as a gathering of scattered tribes. He set up UNIA headquarters there and began speaking at Liberty Hall, addressing packed audiences of workers, domestics, porters, and clerks.

His message was simple but seismic: “Up, you mighty race; accomplish what you will!” He told migrants that their movement was not random — it was part of a historic reawakening. They were not just poor people chasing wages; they were citizens of a great people preparing to reclaim their dignity.

“Garvey told us we weren’t lost. We were exiles returning, in our minds, to a home we had never seen.” — UNIA member, 1923 interview

UNIA membership cards, parades, and the Negro World newspaper all reinforced this sense of belonging. In a strange city where landlords and bosses saw them as replaceable, Garvey saw them as irreplaceable — the builders of a future Black nation.

- Garvey encountered a Harlem crowded with displaced and hopeful people.

- He reframed their migration as part of a larger story of racial destiny.

- UNIA practices turned migrants into members of a global community.

Migration as a Spiritual Journey

Garvey instinctively spoke the language of the Bible Belt migrants who filled his halls. He likened their movement to the Exodus — leaving a “Pharaoh” South for a promised land. But unlike the old story, this promised land was not just the North; it was a restored sense of African worth, wherever they lived.

Many Southern migrants already understood their lives as part of divine drama. Preachers had long preached about Canaan, bondage, and deliverance. Garvey added a Pan-African twist: if God was on their side, then Africa and all her scattered children would rise.

“The people left the South with Bibles and dreams, and Garvey gave them a map.” — Reggae Dread Commentary

For Caribbean migrants raised under the British flag, Garvey’s words translated colonial frustration into righteous purpose. Their journey to the U.S. no longer felt like a one-way escape, but a training ground for a global mission.

- Garvey spiritualized migration, connecting it to biblical and historical narratives.

- He turned economic relocation into a sacred, purposeful journey.

- This framing resonated deeply with both Southern and Caribbean migrants.

The UNIA: Church, School, and Embassy

For a migrant arriving in Harlem, the UNIA hall was a lifeline. It functioned as:

- Church — with hymns, prayers, and moral messages.

- School — offering lectures on history, economics, and public speaking.

- Job center — where members shared leads and business opportunities.

- Embassy — representing Black people as a collective on the world stage.

At meetings, migrants learned to chair sessions, keep minutes, and debate resolutions. Women led auxiliaries, youth brigades rehearsed drills, and business committees discussed ventures like the Black Star Line. In these spaces, people who had rarely been allowed to speak publicly found their voices.

“The UNIA was our first school of nationhood.” — Harlem elder, 1970 oral history

- UNIA halls provided practical support and political education.

- Migrants built leadership skills they would use in later movements.

- The organization acted as a surrogate homeland institution for a people in motion.

Tensions and Unity Across Cultures

The Great Migration didn’t erase differences; it forced them into tight spaces. Southern-born and Caribbean migrants sometimes clashed over accents, customs, and class. Some African Americans felt West Indians looked down on them; some islanders felt misunderstood by “country” Southerners. These tensions showed up in workplaces, churches, and even UNIA meetings.

Garvey’s emphasis on race before nationality — Black first, then Jamaican, American, Trinidadian — was a deliberate attempt to rise above these frictions. In UNIA rituals, all were “Africans at home and abroad.” Flags, uniforms, and anthems were designed to highlight shared identity rather than local difference.

“Garvey made us realize we were one people — just born in different ports.” — UNIA delegate, 1922

This did not magically end conflict, but it created a common language for working through it. The experience of cooperating across regional and national lines in Harlem prepared many future leaders for the pan-national politics of independence movements and civil rights coalitions.

- Migration intensified cultural differences, but also made Pan-African unity necessary.

- Garvey’s rhetoric of shared African identity provided a bridge.

- UNIA’s cross-cultural collaboration became a training ground for future global activism.

Legacy: From Harlem to Home

By the late 1920s, Garvey’s U.S. chapter had been weakened by government repression and internal problems, and he was eventually deported. The Great Migration, however, continued. Millions more would move north and west in later decades. Yet the mental map Garvey sketched remained on the walls of Black imagination.

Later leaders — from Malcolm X to Kwame Nkrumah — inherited communities already shaped by migration and Garveyism. The idea that Black people worldwide shared a fate, and that “home” might be both a physical and spiritual place, informed everything from decolonization campaigns to Rastafari and roots reggae.

“Every train that left the South was part of the same journey Garvey described — the journey home to ourselves.” — Reggae Dread Reflection

For today’s readers, the story of Garvey and the Great Migration is more than history. It is a reminder that displacement can become destiny when people find language, leadership, and love big enough to hold their pain. Garvey did not build a perfect homeland; he did something more enduring — he taught a scattered people how to think of themselves as a nation in motion.

The Great Migration moved Black bodies; Garvey’s vision moved Black minds. Together they turned upheaval into awakening, and mapped a path from exile to identity that still guides the African Diaspora today.

Read next in the “Marcus Garvey in New York (1916–1924)” series: