🔥 Introduction: From St. Ann to the Heart of Jamaican Music

When Winston Rodney left St. Ann and made his way to Kingston, he did not arrive as a star, a professional singer, or even a man familiar with the mechanics of the recording business. He arrived with nothing except conviction — and the unforgettable advice given to him by Bob Marley: “Check Studio One.” That moment, casual in appearance, became one of the central turning points not only in Burning Spear’s journey, but in the evolution of roots reggae itself.

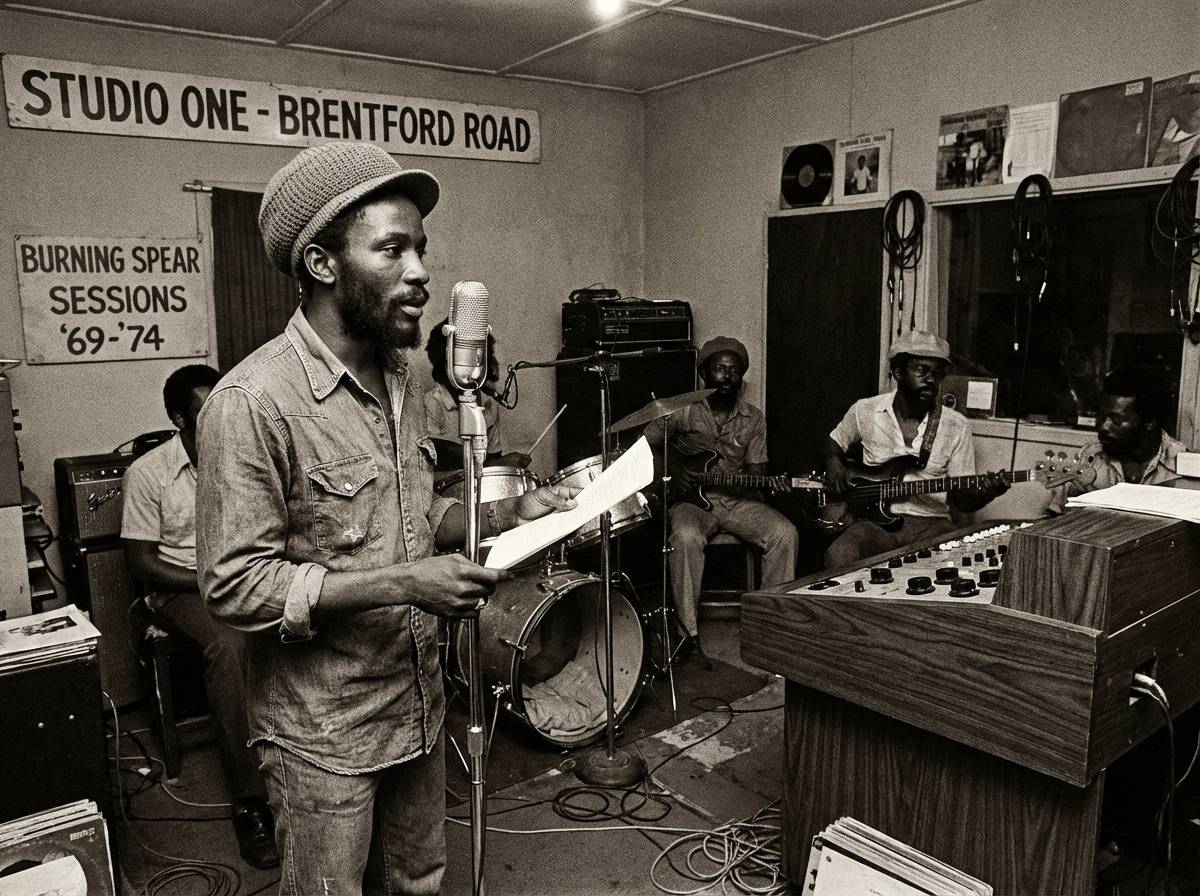

Part 2 of this biography chronicles the years 1969–1974 — a period defined not by fame, but by formation. These were the years when Spear found his voice, developed the trio sound, recorded his debut single “Door Peep,” and learned firsthand how the Jamaican music industry worked — and how it did not work in favor of artists. It was in this pressure that Spear’s commitment to message over profit hardened into something unbreakable.

To understand Burning Spear’s later independence, ethics, and militant stance toward ownership and artistic control, one must begin with Studio One: with the raw sound, the brutal conditions, the uncredited musicians, the lack of royalties — and yet, with the profound sense of destiny that surrounded every song recorded on that famous Brentford Road property.

📍 Arriving at Studio One: The Audition That Changed Everything

Coxsone Dodd – The Gatekeeper

Studio One, owned by Clement “Coxsone” Dodd, was already legendary by 1969. It had produced The Wailers, Delroy Wilson, The Heptones, The Skatalites, and countless foundational records in ska, rocksteady, and early reggae. For many aspiring singers, Studio One was the Mount Zion of Jamaican music. If Coxsone approved you, the entire industry took notice.

But Studio One was not for the timid. Hundreds auditioned. Only a handful passed. Success required something more than talent — it required presence, conviction, and a sound that could withstand Coxsone’s rigorous standards.

“Door Peep Shall Not Enter” — A Song of Warning and Vision

Burning Spear’s first recording, “Door Peep Shall Not Enter,” came after auditioning with Rupert Willington, a fellow St. Ann singer who would become one of his first harmony partners. Instead of imitating popular singers or chasing commercial trends, Spear delivered an incantation — a sparse, haunting, chant-like declaration that seemed to rise up from the earth itself.

Nothing about the record resembled pop. There were no romantic themes, no fast rhythms, no sweet harmonies. It sounded ancient and inevitable — as if the song had existed long before anyone recorded it. Even in its simplest form, the message was unmistakable: spiritual vigilance, historical memory, and moral integrity.

“Some people never give Jah the thanks for life.”

— Burning Spear, “Door Peep” (1969)

With that first record, Burning Spear established what would become a lifelong approach to songcraft: repetition as ritual, simplicity as power, voice as testimony.

👥 The Formation of the Burning Spear Trio

The First Lineup: Rodney, Willington & Hinds

While Burning Spear would later become known as a solo artist, his first recordings featured a three-part harmony group. The original lineup was:

- Winston Rodney – Lead vocals

- Rupert Willington – Harmony

- Delroy “Bro Fred” Hinds – Harmony

The trio format was a natural structure in Jamaican music — following a tradition established by The Wailers, The Maytals, The Melodians, and others. But Burning Spear’s trio did not depend on glamorous harmonies or crowd-pleasing arrangements. Their sound was more like a ritual chant, a sonic circle, a collective invocation.

The Role of Harmony in Spear’s Message

Unlike other harmony groups, where harmonies adorned the lead vocal, the Spear trio used harmonies to deepen the chant. They did not sing to decorate the melody — they sang to amplify the message. When Rodney sang of Zion, Africa, or Garvey, the harmonies transformed the words into collective memory — a kind of liturgical reggae.

This approach would later make the “Marcus Garvey” and “Man in the Hills” albums feel less like songs and more like testimonies, sermons, or ancestral communications.

🎶 The Early Studio One Sessions: The Birth of a Sound

Recording Conditions and Industry Realities

Studio One sessions were notoriously fast-paced. Musicians were expected to record songs quickly, often with no rehearsal, while Coxsone Dodd directed tone and arrangement from the control booth. Payment came in the form of a small upfront fee — royalties were rare.

Burning Spear was not given special treatment. Like many artists of the time, he recorded under pressure, with minimal financial reward, and without legal control over his master tapes. But unlike many of his peers, he left Studio One not bitter, but determined. The experience did not defeat him — it sharpened his resolve.

Key Songs from the Era

- Door Peep

- Zion Higher

- Rocking Time

- Swell Headed

- We Are Free

- He Prayed

Each of these songs contains the DNA of Spear’s later work: African aspiration, spiritual defiance, memory of enslavement, and a deep-rooted belief that history and identity are not abstract subjects — they are urgent matters of survival.

💰 The Exploitation Problem: Lessons Learned

Despite Studio One’s brilliance, the label also became the center of one of reggae’s great paradoxes: songs of liberation recorded within systems of economic exploitation. Most artists never saw proper royalties. Some were never credited for their work. And because the label owned the masters, artists had no legal recourse.

Burning Spear understood two things very early:

- No producer, no matter how powerful, could own his message

- True musical independence would eventually require controlling distribution

These painful lessons eventually led Spear to create his own label, Burning Music, years later — but the seed was planted right here, inside the Studio One trenches.

📀 The First Full-Length Albums (1973–1974)

Burning Spear (1973)

This debut album, released by Studio One, is one of the most raw and intimate recordings in Spear’s catalog. It includes early versions of the songs that would later define him, including “Door Peep,” “Swell Headed,” and “We Are Free.”

It is not the Spear most fans know today. There are no powerful horn lines, no expansive arrangements, no polished production. But the essence is unmistakable. The attitude is uncompromising. The voice is already prophetic.

Rocking Time (1974)

If the first album was a declaration, Rocking Time was a refinement. The title track introduced a slightly more melodic rhythm, and songs like “Foggy Road” captured the tension between hope and sorrow that defines much of Spear’s writing.

These albums did not chart internationally. They did not earn major airplay. Yet they are now considered sacred texts among roots scholars. They capture the artist before the world noticed him — and before the industry attempted to reshape him.

📡 Spiritual Development & Philosophical Breakthroughs

The Emergence of the Garvey Consciousness

Although Burning Spear’s Studio One period did not explicitly focus on Marcus Garvey yet, the foundation was clearly forming. The language of deliverance, African identity, resistance to oppression, and historical memory permeates the lyrics even before Garvey is named.

By the time the album Marcus Garvey would arrive in 1975, the ideology was already in place. Studio One became the silent training ground for a future movement — not only musical but intellectual and cultural.

Chant as a Weapon

Just as Nyabinghi drumming is not performed for entertainment, Spear’s chant-based vocals served a ceremonial purpose. They were an alternative to Western melodic structures — an African approach to voice, rhythm, and memory.

While other singers in the early 1970s pursued love songs or dance hits, Spear used repetition, tonal variation, and ritualized phrasing to invoke history — not merely describe it.

🏙️ Kingston vs. St. Ann: The Tension Between Two Worlds

Many of Spear’s songs from this period reflect a contrast between rural harmony and urban struggle. St. Ann represented origin, clarity, and grounding. Kingston represented opportunity — but also Babylon, exploitation, and the danger of losing one’s identity.

Burning Spear was not merely a man who traveled from country to city. He was a vessel carrying rural values into the heart of the cultural machine, refusing to let the machine reshape him.

🔑 Why the Studio One Years Matter

Even though many fans begin their Burning Spear journey with Marcus Garvey, the Studio One era forms the essential blueprint. Without this chapter, the later chapters cannot be understood correctly.

The Studio One period is important because:

- It established the chant-based Spear vocal identity

- It introduced key themes later developed in the Garvey albums

- It revealed the power and limitations of the Jamaican music system

- It solidified Spear’s commitment to message over commercial appeal

- It prepared him for independence, activism, and global leadership

This was the soil where the Spear was planted — before it was sharpened, before it was lifted, before it was hurled into history.

📎 Conclusion: A Foundation of Fire

By 1974, Burning Spear was no longer a beginner. He was a vessel of purpose. He had recorded dozens of tracks, developed a unique vocal style, suffered through the inequities of the industry, and emerged with a message that had only grown stronger.

The years that followed would bring international acclaim, political clarity, and historical urgency. But none of that would have mattered without this foundation.

In 1969, Spear walked into Studio One as a young man from St. Ann. By 1974, he walked out as something else:

A messenger.

Next in this series: The world changes — and Burning Spear becomes the torchbearer of Garveyism in reggae.

Continue to Part 3: Marcus Garvey Era & Global Breakthrough (1975–1976)