Rastafari begins as a refusal

To understand Rasta culture, you have to understand the word behind it: refusal. Not refusal as childish rebellion—refusal as spiritual adulthood. Refusal to accept a story that says Black people are born to be ruled, corrected, renamed, and robbed of memory. Refusal to accept a “civilization” that demands you straighten your hair, quiet your language, soften your drum, lower your eyes, and thank the system for the privilege.

Rastafari rises in Jamaica during a time when many people were taught to measure themselves by whiteness— by the standards of a colonial order that never planned to treat them as full human beings. The movement didn’t start as a brand. It started as a counter-meaning. If Babylon is the system that crushes spirit, then Rasta becomes the spirit that refuses to be crushed.

ReggaeDread lens: Rasta culture is not a trend. It is a survival philosophy built into a lifestyle.

The Jamaica that gave birth to Rasta

Jamaica’s story—like much of the Caribbean—is written with sugar and blood. Plantation economics created wealth for empire while keeping the laboring majority under pressure. Even after emancipation, the social order didn’t suddenly become fair. Power stayed concentrated. Land stayed unequal. Wages stayed tight. The institutions—education, church, government—often carried a colonial mind even when the island’s people carried African memory in their bones.

When we say Rastafari begins in Jamaica, we’re also saying it begins in an emotional climate: people searching for dignity, searching for a language that tells the truth about their condition, searching for a spiritual framework that doesn’t demand self-erasure.

Three pressures that shaped the early movement

- Economic pressure: hard work with little reward, and a system built to keep the majority “in place.”

- Psychological pressure: colonial education and religion teaching Black inferiority directly or indirectly.

- Cultural pressure: African identity treated as backward while European identity was treated as “proper.”

Why prophecy mattered so much

Prophecy is powerful when a people are under pressure because it offers a map through darkness. But Rasta prophecy is not only fortune-telling. It’s interpretation. It’s reading the moment and saying, “This suffering is not the final word.” It’s claiming that history contains a spiritual current moving beneath the surface—an invisible river that eventually breaks through concrete.

In the early Rasta imagination, scripture and African consciousness begin to overlap. The Bible is read with new eyes, not as a tool of submission but as a weapon of liberation. Verses that once were used to justify slavery are flipped. The language of Zion, Babylon, exodus, and redemption becomes a vocabulary for political clarity and spiritual survival.

Biblical language becomes social language

| Word | In the Rasta sense | What it points to |

|---|---|---|

| Babylon | Oppressive system, confusion, exploitation | Colonial and post-colonial power structures |

| Zion | Spiritual home, liberation, rightful identity | Africa/Ethiopia as symbol of return and dignity |

| Exodus | Leaving mental slavery and external domination | Freedom as a process, not a single event |

| Reasoning | Collective thinking and spiritual conversation | Community knowledge-building |

The movement before the movement: long roots beneath the ground

Rastafari didn’t appear in a vacuum. It is part of a larger Black Atlantic story: resistance, spiritual creativity, and the search for African-centered identity after centuries of displacement. Jamaica held many streams that fed the river: Revival traditions, Kumina influences, Ethiopianism in churches, Garveyism in political thought, and the day-to-day wisdom of people who knew the system was built against them—even if they didn’t have the academic language to describe it.

In the early twentieth century, ideas were moving: Pan-African thought, Black pride movements, diasporic organizing. The island was not isolated. It was listening to the world, reading newspapers, hearing speeches, absorbing sermons, watching the contradictions of empire.

What Rastafari does that feels new

- It declares identity as sacred: Blackness isn’t a problem to fix; it’s a truth to honor.

- It spiritualizes liberation: freedom is not only political—it’s mental, cultural, and bodily.

- It builds lifestyle around belief: not just “what you think,” but “how you live.”

How a “message” becomes a community

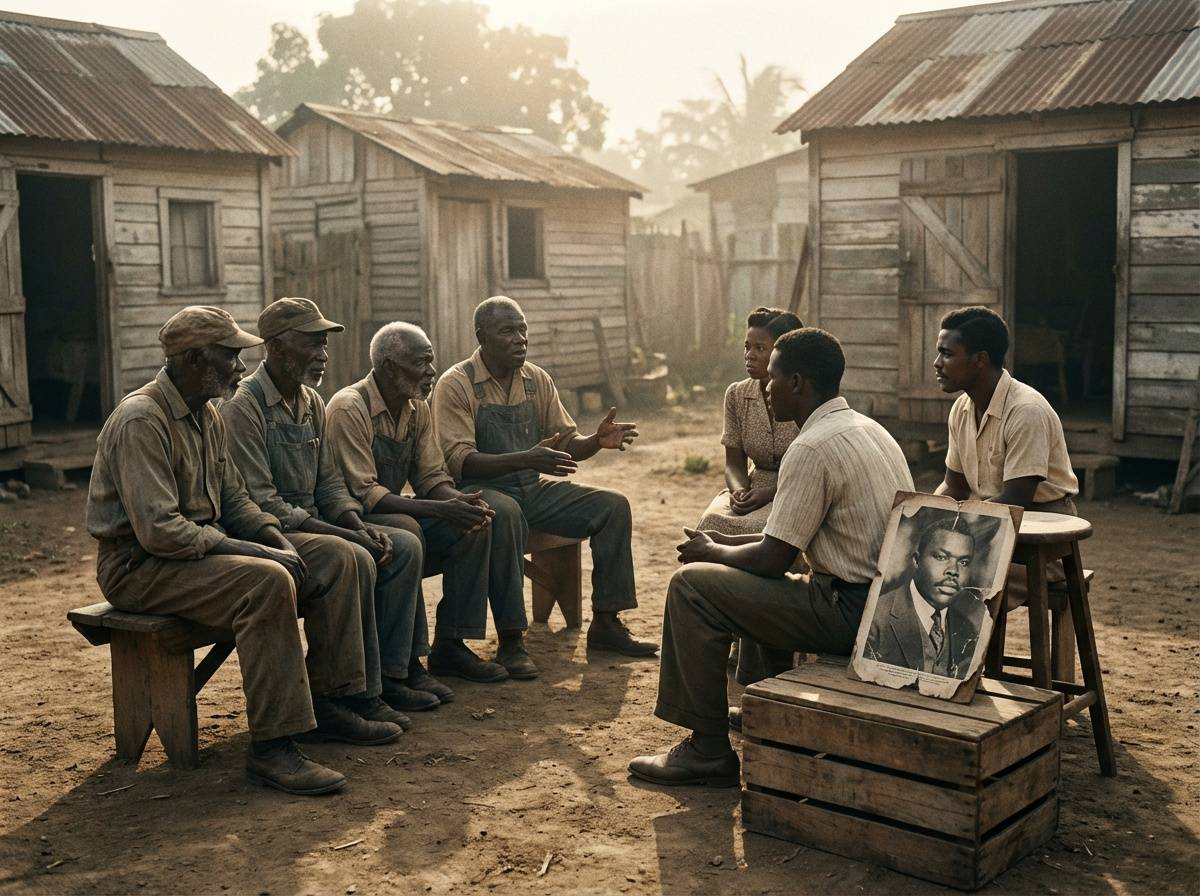

Every movement has a phase where it’s more idea than structure. Early Rastafari existed like that—circulating through conversations, street corners, yards, small gatherings, and sharp disagreements. Some people were drawn to the message. Others feared it. Authorities often treated it as threat. Churches often called it heresy. Middle-class society often mocked it. Yet the message survived because it spoke to a hunger that mockery couldn’t feed.

When a message becomes community, it creates markers: language, symbols, rituals, distinctive ways of seeing. The earliest brethren formed identity not by copying a uniform but by shaping a mindset. Their “culture” developed as an answer to pressure—what does it mean to be free in a place built to manage you?

Early identity markers (in seed form)

- Speech: new ways of speaking to express dignity and spiritual presence

- Dress: a turn away from colonial respectability politics

- Diet: movement toward purity and discipline (later formalized in Ital traditions)

- Gathering: reasoning, chant, and communal reflection

The struggle for respect: why Rasta was targeted

Rasta challenged the foundations of respectability culture. It refused the idea that “proper” equals “European.” It challenged the authority of institutions that had long shaped Jamaican society. It proposed that the oppressed have a right to interpret scripture, history, and identity for themselves—without asking permission.

When a movement challenges the mental order of a society, it often gets policed more aggressively than you’d expect. Not because it is violent, but because it reveals contradictions. Rasta forced uncomfortable questions: Who benefits from the current system? Why is African identity treated as inferior? Why is suffering normalized? Why is spiritual authority concentrated in institutions that don’t serve the poor?

Important clarity: Rastafari has diverse mansions and interpretations. What you see in one community does not automatically represent all Rastas everywhere.

Rasta culture is built on “livity,” not performance

One of the most misunderstood aspects of Rastafari is that it’s often treated like style before it’s understood as substance. But Rasta culture is anchored in livity—the principle that your life itself is the teaching. The words you speak, the food you eat, the way you reason, the way you resist Babylon, the way you honor community— these are not accessories. They are the culture.

Livity is the discipline of alignment. If you say you are about truth, how do you live truth? If you say you honor life, how do you treat your body? If you say you reject Babylon, how do you avoid becoming Babylon in your own house—through greed, vanity, or exploitation?

Three pillars of early livity thinking

- Purity: not perfection, but an effort to keep life clean and intentional

- Dignity: refusing self-hate and refusing social scripts that demand self-erasure

- Reasoning: community conversation as a practice of spiritual and intellectual freedom

The seed of later chapters: music, language, diet, and identity

Part 1 is the foundation—because every later expression comes from this origin energy. When you reach the reggae chapter (Part 7), you’ll see how music becomes a broadcast system for Rasta worldview. When you reach language and symbolism (Part 8), you’ll see how a people protects meaning by shaping words and signs. When you reach lifestyle (Part 9), you’ll see livity become daily practice: reasoning, discipline, community rhythm.

The origin story matters because it reminds us that none of these elements were invented for aesthetics. They were built for survival, dignity, and spiritual clarity.

A simple origin timeline (high-level)

This is a simplified map to keep the flow. Later chapters zoom into the details.

- Colonial pressure and cultural erasure: long-term social conditions set the stage.

- Rise of Black dignity and Pan-African thought: ideas circulate in Jamaica and the diaspora.

- Prophetic interpretation and new identity language: scripture, Africa, and liberation become connected.

- Early brethren form community markers: gathering, reasoning, lifestyle choices, and a distinct worldview.

- Rasta develops “expression systems”: chant, drum, later reggae; language and symbols as protection of meaning.

Key takeaway: Rastafari begins as a response to oppression—but grows into a complete cultural system: belief, lifestyle, language, music, and identity.

FAQ: Rasta culture origins

Is Rastafari a religion, a culture, or a political movement?

Rastafari can be understood as all three, depending on context. It is spiritual at its core, cultural in its lifestyle expression, and political in its resistance to oppression. Many communities emphasize different aspects, but the throughline is livity—life as message.

Why is the Bible so present in early Rasta thinking?

Because scripture was already present in Jamaican life, but Rasta read it differently—through liberation, identity, and prophetic interpretation. Biblical language becomes a vocabulary for describing oppression (Babylon) and freedom (Zion) in a way people could hold onto.

Is “Babylon” just a slang word?

In Rasta worldview, Babylon is a serious concept: systems of exploitation, confusion, and domination—especially those that demand mental submission. It’s not a casual insult; it’s a critique of structures that crush dignity and distort truth.

Why does the origin story matter today?

Because modern stereotypes often detach Rasta style from Rasta meaning. The origin story restores context: dread, diet, language, and music are not random. They are expressions of a worldview built under pressure.

Next (Part 2): We step into the wider Black Atlantic mind—Marcus Garvey, Ethiopia, and the long memory that shaped Rasta consciousness into a global idea, not just a local response.

Continue the series: Part 2 — Marcus Garvey, Ethiopia & the Long Memory